Trauma

Trauma

“Trauma is not in the event itself; rather, trauma resides in the nervous system. Trauma happens when any experience stuns us like a bolt of lightening. It overwhelms us, alters us and disconnects us from our bodies. We feel utterly helpless and hopeless. It is as if our legs are knocked out from under us.” Peter Levine and Maggie Kline

Trauma and The Freeze Response

Dr Peter Levine and Dr Maggie Kline in Trauma Through a Child’s Eyes(1) state:

When the primitive parts of the brain perceive danger, and we are at a disadvantage due to size, age or ability, we are biologically programmed to freeze. There is no conscious choice and we go limp when flight or fight is either impossible or perceived to be impossible. Freeze is the last ditch, default response to an inescapable threat. Children, because of their limited capacity to defend themselves, are particularly susceptible to freezing and are vulnerable to being traumatised.

Underneath the freeze response is a variety of physiological effects. What must be understood about the freeze response is that although the body looks inert, those physiological mechanisms that prepare the body to escape may be on “full charge”. The sensory-motor-neuronal blueprint that was set into motion at the time of threat is paradoxically thrown into a state of immobility or “shock.” Underlying this situation of helplessness is an enormous vital energy. This energy lies in wait to finish what has been started. In addition, very young children tend to bypass active responses and go right to shutdown.

Children living with disability or neurodivergence are likely to freeze during traumatic experiences like sexual abuse. Research shows that non-verbal or profoundly intellectually impaired children are more likely to experience more serious offences including penetration and fewer minor offences(2). Children with disability who have higher needs, are associated with increased risks of sexual abuse than children with lower needs(2). Children with higher needs who are more dependent on caregivers are more at risk of repeated offences, higher severity of sexual acts, increased use of force and the tendency of physical injuries to be inflicted during abusive incidents(2). Though, children with disability or neurodivergence who have lower needs are more likely to be sexually abused than neurotypical children(2).

Trauma and Epigenetics

Sacred Justice’s programs are based on groundbreaking research by leading experts on trauma; Dr Gabor Mate, Dr Peter Levine and Maggie Kline. Research shows that trauma caused by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) impairs a child’s neurobiology well into adulthood.

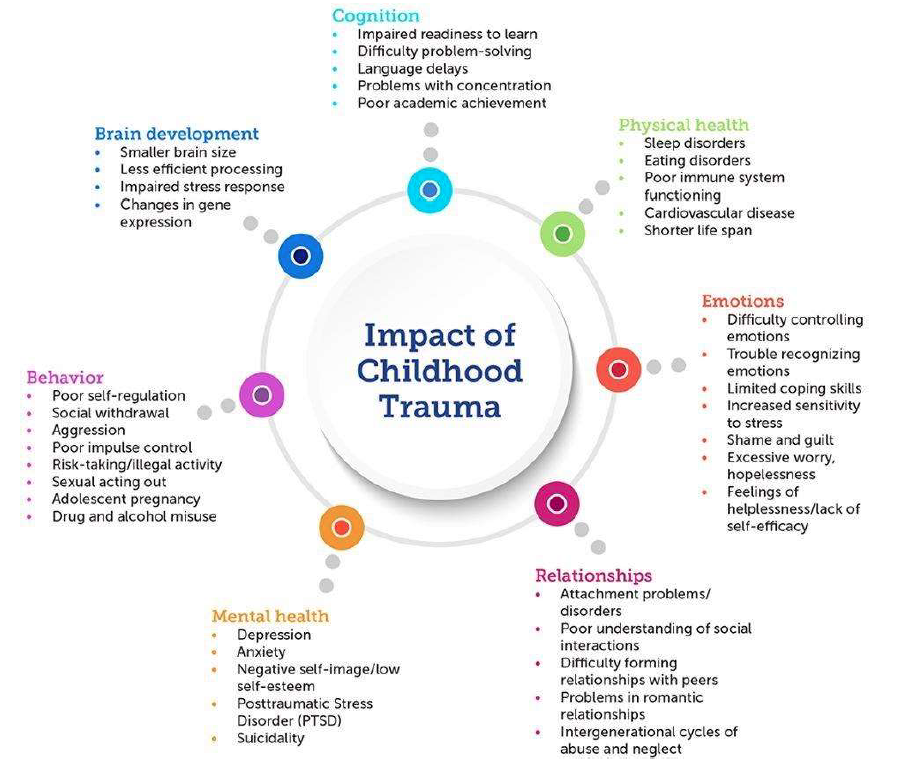

Toxic stress response occurs when a child experiences frequent and prolonged neglect or abuse. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems and increase the risk of stress-related disease and cognitive impairments well into adult years(3).

Negative early experiences can cause long-term genetic, brain, behavioural, and hormonal changes that can affect not only the abuse victim but also their descendants(3). Dr Regina Sullivan and Elizabeth Lasley(4) discuss the effects of abuse on a child’s genes:

Traumatic experiences such as abuse can work their way into a child’s genes. This fact may come as a surprise, since most of us think of genes as something we are born with. The genetic material we receive from our parents is important, but how our caregivers treat us as we grow can greatly influence the way the genetic material is “read” and used. The influence of outside-world factors on our genes is known as epigenetics.

The concept of epigenetics helps explain why so many effects of child abuse do not become apparent until adolescence or adulthood. It may also hint at why some abused children grow into abusers themselves. Neglect or emotional or physical abuse that produces either heightened or prolonged activation of the stress system results in later-life difficulties. We know that the brain responds by changing its structure, gene expression, and function.

The image below shows the impact of childhood trauma(20):

Trauma and Brain Development

Imaging studies of abuse survivors show that brain areas controlling emotion and cognition are abnormal, both anatomically (they are generally smaller) and functionally(4). The devastation resulting from abuse often will not become fully apparent until the child is well into adolescence(4). By adolescence, 80 percent of abused children will be diagnosed with a major psychiatric illness(4).

Evidence shows that social and emotional information is processed differently among children that have experienced abuse. The amygdala, an area of the brain associated with the automatic (pre-conscious) processing of emotional information, has been shown to be over-responsive to emotional stimuli(6). Children who have been exposed to traumatic environments have reduced thickness in an area of the brain responsible for emotional processing of social information (ventro medial Prefrontal Cortex, vmPFC) suggesting this area is less developed in these children compared with non-abused children(6).

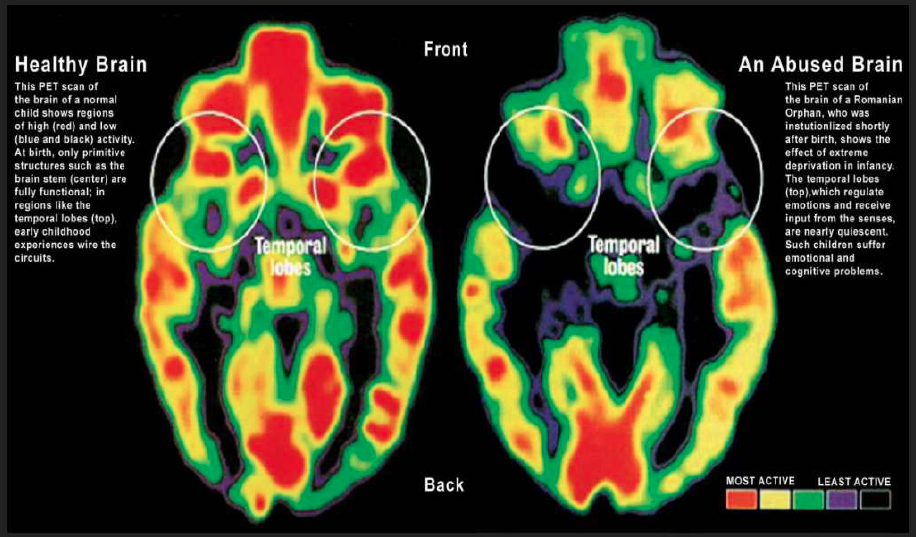

The image below shows a PET scan of two children’s brains; the left brain hasn’t experienced abuse and the brain on the right is of a Romanian orphan who has experienced neglect and sensory deprivation. The brain on the right shows that the temporal lobes are dormant of activity indicating that this child would have difficulty regulating emotions, have poor impulse control, socially withdraw, have low self esteem, pathological behaviours such as tics, tantrums, self harm and poor intellectual functioning (7).

This study showed that institutionalised children had smaller brains and a lower volume of gray matter (cell bodies of neurons) and white matter (nerve fibers that transmit signals between neurons)(7). If an institutionalised child was moved into foster care, they did recover some of the white matter volume over time(7). But, their gray matter volume stayed low. These brain changes led to an increased risk of ADHD symptoms(7).

Source: The High Cost of Child Poverty, Sean Casey, August 2013. Visit source

Trauma and Memory Recall

There is evidence that memory is affected by trauma and adversity. Compared with non-abused children, children with abuse-associated PTSD may also show less effective activation of this area of the brain during a memory recall task(7). Neuropsychological studies of children also support the idea that memory is affected by exposure to trauma and other adversity.

Studies of children who have been diagnosed with PTSD in the context of abuse also suggest they may experience memory difficulties, but the findings depend on the way memory is measured(7). This brings up an important issue: the ability of children to recall and verbalise memories of repeated, long term child sexual abuse to legal authorities and child protection agencies. Some parents hesitate to involve authorities because the child’s story seems fuzzy, disjointed or conflicting.

Traumatic Amnesia

The automatic repression of painful emotions is a helpless child’s prime defence mechanism and can enable the child to endure trauma that would otherwise be catastrophic(8). The unfortunate consequence is a wholesale dulling of emotional awareness. In an act of self-preservation, the brain limits recall. Memories of the event may return in fragments or random waves. Some events may be blocked temporarily or permanently by a phenomenon known as Traumatic Amnesia(9).

Traumatic Amnesia is not considered by child protection, legal and judicial systems when assessing children’s disclosures. There seems to be a common theme occurring within the Australian child protection and legal system that children’s disclosures are not believed, despite recent research by showing that 98% of children tell the truth about their abuse(10).

Children in Out of Home Care (Foster Care)

Children who are placed in out-of-home care are likely to have experienced a range of early-life adversity. The range and complexity of these adverse circumstances are well known to practitioners, and they include trauma, abuse, neglect and antenatal substance exposure(6). Research suggests that the behavioural difficulties of many children in care are underpinned by cognitive vulnerabilities related to exposure to adverse and traumatic events in childhood(6). Children who are placed in out-of-home care experience higher levels of behavioural and mental health issues than children from similar backgrounds who are not in placed in care(6).

Research and Statistics

There is a lack of research in Australia on the sexual abuse of children in foster care, group homes, out of home care, residential facilities and respite centres. Particularly, children with disabilty or neurodivergence or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with disability in out of home care. Children living without either parent (foster children) are 10 times more likely to be sexually abused than children that live with both biological parents(11). Children with disability or neurodivergence are at an even greater risk if they live in foster care, government care or residential care(11). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are in out-of home care at 11 times the rate than non-Indigenous children(12).

PTSD and Autism Misdiagnosis

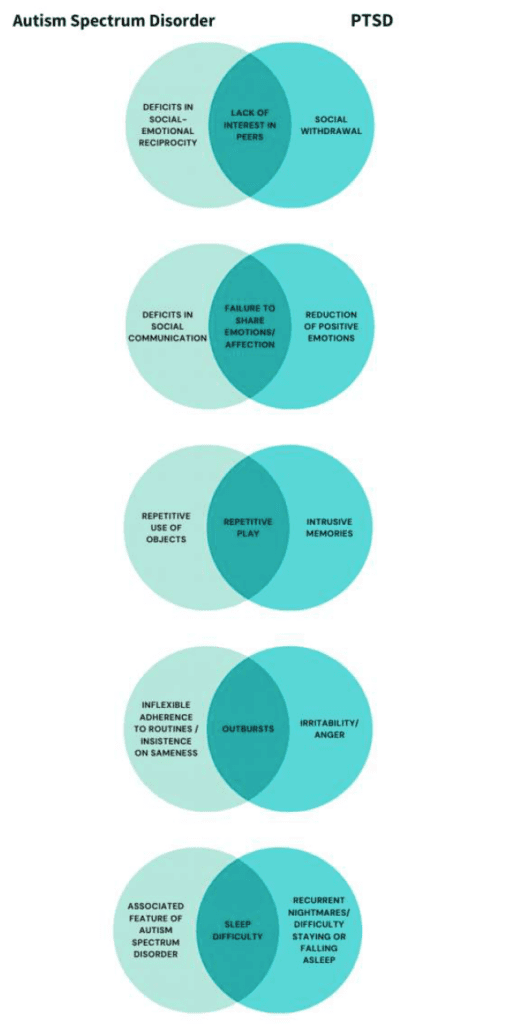

A child’s response to trauma can sometimes mirror the signs of Autism. What look like typical Autistic traits, such as repetitive play, difficulty communicating with others, or outbursts of anger or frustration, might actually be the child’s way of dealing with intrusive thoughts and feelings after trauma. If a child’s behaviour can be explained by Autism, and there is no knowledge of a trauma having taken place, it’s possible for a PTSD diagnosis to be missed(14). By mimicking Autism, PTSD can hide in plain sight. Autistic children may find it hard to communicate with others or struggle to recognise how other people are feeling(14). They may be sensitive to loud noises or bright lights, and feel anxious in unfamiliar situations.

Children with PTSD may behave similarly, but for different underlying reasons. Children who experience trauma when they are young may display Autism-like behaviours that fit the timeline for an Autism diagnosis, which tends to occur around early school-age(14). In the absence of trauma-informed assessment, Autism can sometimes be the default diagnosis. It is possible for Autistic people to experience PTSD, just like anyone else. While children may be misdiagnosed with Autism instead of PTSD, both adults and children who have Autism and PTSD may struggle to get the additional diagnosis(14). Children with ADHD and Autism are more likely to develop PTSD(15). The diagram below shows the overlapping symptoms of PTSD and Autism(14).

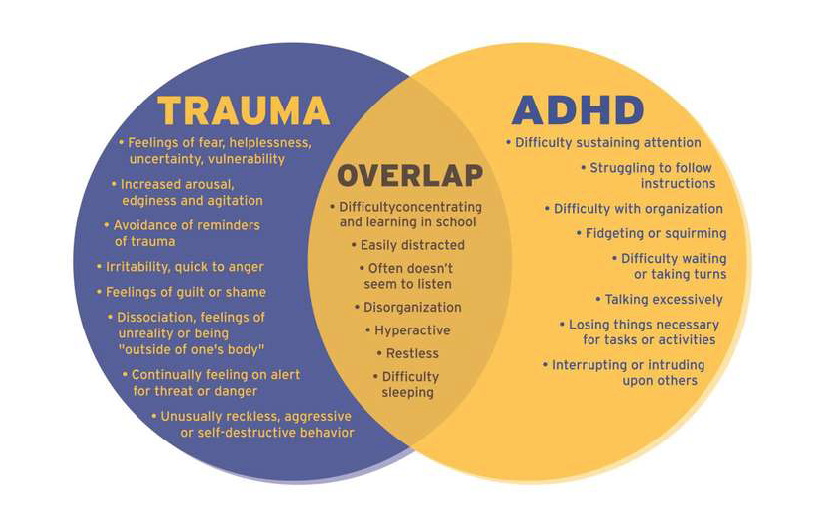

Trauma and ADHD Misdiagnosis

Childhood trauma is linked to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) because they share similar symptoms that are often confused and misdiagnosed when they are actually displaying the symptoms of traumatic events(16). Each also amplifies symptom severity in the other. Children who have experienced four or more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are three times as likely to take ADHD medication when compared to children with less than four ACEs(16). Among children who experience trauma, intrusive thoughts or memories of trauma (; feeling like it is happening all over again) may lead to confused or agitated behaviour which can resemble the impulsivity of ADHD(16). Trauma, if present with ADHD, can exacerbate ADHD symptoms. At the same time, ADHD may also increase the risk of exposure to trauma(16).

Traumatic stress and ADHD affect the same areas of the brain, which can complicate ADHD symptoms and assessments in children(16). In response to trauma, a child’s developing brain can become programmed to ‘look out’ for behaviour, activities or events that they perceive as threatening. This “hypervigilance” can often mimic hyperactivity and distractibility associated with ADHD(17). Trauma can make children feel agitated, troubled, nervous, and on high alert — symptoms that can be mistaken for ADHD(16). Inattention in children with trauma may also make them dissociate, which can look like a lack of focus; another hallmark symptom of ADHD(16).

ADHD and child traumatic stress frequently co-occur with other conditions like mood disorders, anxiety and learning disabilities. What may appear as inattention and “daydreaming” behaviour often seen in ADHD may actually be symptoms of dissociation or subconscious avoidance of trauma triggers(17). Brain development studies for ADHD and child maltreatment show significant similarities in the areas of the brain that are affected (areas responsible for emotional regulation, decision making, memory, social processing and concentration)(17). The diagram below shows the overlapping symptoms of Trauma and ADHD(17):

Trauma Bonding

It is worth mentioning the development of attachment disorders due to childhood abuse. Abuse creates disorganised attachment which affects relationships and connection to others. Many children continue to desire the nurturing and accepting love of an abusive parent, even long after they have been removed from the abusive home environment(18).

Victim Loyalty to the Abuser

Traumatic bonding can happen when a child experiences periods of positive experience alternating with episodes of abuse. By experiencing both positive and extreme negative treatment from a parent, a child can become almost co-dependent. A child will over-identify with the abuser, feel indebted to them and protect them. They feel that he or she ‘needs me’ and they may even allow the abuse to continue to ‘please’ the abuser. Particularly, if the abuser is a parent or step parent. They may cover-up negative emotions in front of the abuser and desire love and affection from the abuser despite being hurt. Sometimes victims may only want the love and affection from the abuser.

Abuse Interspersed with Kindness

Children can become passive to their abuse because they choose to survive rather than escape(19). This can lead the child to see the abuse as normal behaviour. Victims of abuse often develop a strong sense of loyalty to their abuser, despite the fact that the bond is damaging to them(18). An abuser sets up the perfect conditions for trauma bonding by delivering abuse interspersed with kindness and nurturing; isolating the victim from other people’s perspectives; threatening and a belief that there is no other option but to be abused(18).

The victim may having negative feelings for potential rescuers, supporting the abusers’ reasons and behaviours and an inability to engage in behaviours that will assist in their rescue or detachment from their abuser(18). A sexually exploited child is not using the logical part of their brain. They are using the amygdala that is concerned with immediate survival. The brain will respond: “This won’t kill you, so freeze and endure it”(18). This becomes an automatic response to future assaults(18).

Attachment to the Abuser

Children crave attachment. This creates a complex situation when an abuser uses both fear and a loving relationship with the victim to maintain control. When an abuser hurts the victim, although the victim may disclose the abuse to third parties, the trauma bond means that the victim may also wish to receive comfort from the very person who abused them(18). If the abuser re-bonds with the victim, it is likely that the victim will return to the abuser and cut contact with the third party(18). Any contact the child has with the abuser (even a text or Facebook message) can re-bond the victim to the abuser.

To break the trauma bond, a victim needs to have alternative healthy relationships available and be isolated from the abuser for a significant period of time(18). This allows the child time to heal and come to terms with the trauma they experienced, re-shaping the nature of future relationships. Unfortunately, the concept of trauma bonding isn’t considered when Child Safety Departments or Police manage child disclosures and subsequent child protection orders.

Reunification

The Policy of Reunification within Child Safety in Australia is a telling example of re-traumatisation. Child victims are often forced to spend time with their abuser through the process of Reunification. Even if the child has disclosed sexual abuse by the parent, the parent is legally entitled to have an active caregiver relationship with the child. This policy is strongly adhered to by Child Safety and creates re-traumatisation. One example includes a child who was abused from 2 to 7 years old. After disclosure, Child Safety pushed a reunification agenda for the abusive parent to have full time care. After 2 years of this relentless agenda, the Office of the Public Guardian stepped in at the last minute to prevent full time reunification. Through the reunification policy, the abusive parent is still entitled to weekly visitations. This is a common occurrence in Child Safety policy.

Trauma Informed Care (TIC) and Post Traumatic Growth

A Trauma Informed Care approach is integral to educating and caring for children with disability or neurodivergence. Given their vulnerability to sexual and other abuses, it is common for these children to experience clusters of Adverse Childhood Experiences. In a Trauma Informed Care approach, we view behaviours as symptoms of underlying emotional or mental health issues. Crying, screaming, emotional releases (meltdowns), self harm, aggression and violence are viewed as ‘resources’ that children utilise to express their emotions or stored trauma.

Children Respond to our Nervous System at an Unconscious Level

Offering these children a sense of safety and predictability with our responses to them is the key to reshaping their behaviours. Non-verbal and minimally verbal children can understand us at an unconscious and energetic level: our tone, our intention, our energy and the regulation of our nervous system. Through your body language, facial expressions and tone of voice, your own nervous system communicates directly with the child’s nervous system(1).

Children are astute readers of facial, postural and vocal cues from parents. Neurodivergent children are more astute than most because they have spent their lives trying to understand people’s behaviour to imitate, or to read the social cues of interactions. This is how we connect to non-verbal children without words.

‘Holding Space’

When you become a calm presence around a dysregulated child, your nervous system becomes contagious in a good way(1). You’re allowing the child to experience uncomfortable sensations and you are comforting them, ‘holding space’ for them whilst their bodies progress through the natural cycle of tolerating these sensations, expressing them and completing them.

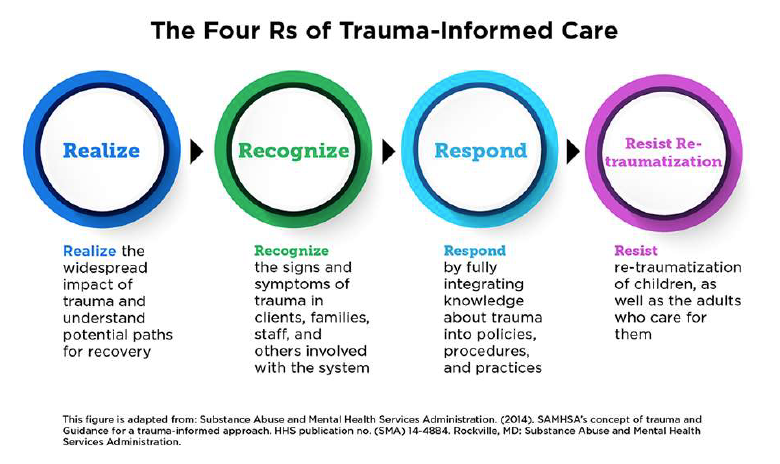

Trauma Informed Care: Applying a ‘Trauma Lens’

Despite its focus on trauma, Trauma Informed Care is inherently a strengths-based perspective that emphasizes resilience instead of pathology (see image below)(20). Providing adults (staff in child service providers, families) with training and professional development on childhood trauma is an important component of implementing Trauma Informed Care. It is essential that adults become aware of the prevalence and impact of trauma, and learn to apply a “trauma lens” (; gain the capacity to view children’s difficulties in behavior, learning, and relationships as natural reactions to trauma that warrant understanding and sensitive care) (20).

Protective and Compensatory Experiences (PACES) and Brain Neuroplasticity

It is possible to re-wire the brain to thrive after traumatic experiences. Research into Protective and Compensatory Experiences (PACEs) show us that having positive experiences increase resilience and protects against the risk for mental and physical illness. Resilience is the process of adapting in the face of tragedy, and Post Traumatic Growth refers to positive changes experienced as the result of adversity in life or a life-altering crisis(21). After trauma, we can work with the neuroplasticity of our brain to restructure them to experience happiness and contentment. The beauty of the human brain is that it is malleable and new neurological pathways can be created.

This is where Sacred Justice steps in by utilising Somatic Experiencing Therapy, Conscious Breath, Meditation, Music, Dance, Martial Arts, Art and other creative activities combined with effective psychotherapy approaches to release emotions, achieve resilience, re-wire the brain and create Protective and Compensatory Experiences that result in Post Traumatic Growth.

References

(1) Trauma through a Child’s Eyes: Awakening the Ordinary Miracle of Healing by Dr Peter Levine and Dr Maggie Kline, 2011, Penguin Publishing

(2)Victimization of Children With Disabilities, Dr Irit Hershkowitz, Michael E Lamb and Dvora Horowitz, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4):629-635, October 2007

(3) When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress, Dr Gabor Mate, 2003, Scribe Publications

(4) Fear in Love: Attachment, Abuse, and the Developing Brain, Dr Regina Sullivan and Elizabeth Norton Lasley, Cerebrum, 2010 Sep-Oct; 2010: 17

(5) Adverse Childhood Experiences, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, July 2016, http://www.samhsa.gov/capt/practicing-effective-prevention/prevention-behavioral-health/adverse-childhoodexperiences

(6) The effect of trauma on the brain development of children: Evidence-based principles for supporting the recovery of children in care, Sara McLean, June 2016, Australian Institute of Family Studies, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/effect-trauma-brain-development-children

(7) The Lasting Impact of Neglect, Kirsten Weir, American Psychological Association, Vol.45 No.6, June 2014 https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/06/neglect

(8) In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, Dr Gabor Mate, 2010. North Atlantic Books

(9) Sandusky case sheds light on complexities of child sexual abuse, Robin L O’Grady and Nicole Matthews- Creech, 2022, https://lacasacenter.org/why-child-abuse-victims-dont-tell/

(10) Child Sexual Assault: Myths, Facts and Stats, Bravehearts, 2022 https://bravehearts.org.au/what-we-do/education-and-training/for-parents/child-sexual-assault-myths-facts/